Book Reviews

You are here – Home – Book Reviews

An occasional series of book reviews for publications members may find of interest.

Sapiens – A brief history of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari Vintage Books (Penguin Random House) First published in Hebrew 2011

ISBN 978-0-099-59008-8

The legendary detective, Sherlock Holmes, said of his brother, Mycroft, that ‘his specialism is omniscience’. A similar compliment might possibly be paid to Yuval Noah Harari, whose bestselling book, Sapiens, purports to provide a ‘brief history of humankind’.

Omniscient or not, Harari takes on the formidable task of tracing the progress, or otherwise, of Homo Sapiens, from the time when this species of human began to move out from his original homelands in East Africa until the present day. He begins the story earlier still. Humans first made their appearance amongst the planet’s creatures about 2.5 million years ago and discovered the vital properties and uses of fire around 800,000 years ago. Although Harari initially refers to this background, the brief which he has given himself is to identify three significant ‘revolutions’ in the development of Homo Sapiens as the dominant species on Earth, each of them being a lurch forward in that career, for better or worse.

The first of these revolutions was the Cognitive Revolution. Although Homo Sapiens had been content to hang around in East Africa for centuries without doing anything very adventurous, he appears to have become more inquisitive and active around 70,000 years ago. With the wanderlust upon him and his head brimming with new ideas, he moved northwards to the Levant, Asia, Europe and, eventually, to the rest of the world, driving all before him. He saw off – we’re not sure how – all the other species of human, such as Neanderthals, and large numbers of other species, too, especially the megafauna. By 45,000 years ago, 90 per cent of Australia’s large species had disappeared, and Sapiens is the most likely culprit for their removal. He didn’t stop there. In about 14,000 BC, he arrived on foot in north-western Alaska from Siberia, then joined by a land mass. When the weather warmed up a bit, tribes moved southwards until they had reached every part of the American continent. Once again, they appear to have done away with the megafauna and much else. How did Sapiens the hunter/gatherer manage to achieve all this? Through gossip, according to Harari. Sapiens had terrific social skills and could organise, and communicate with, large numbers of people in families, tribes, clans or whatever. These groups were also competitive and would take on other groups in battles for the best supplies of food, water and shelter.

Sapiens could not only personally organise groups of up to 150 people, he could control much larger ones through the invention of myths or beliefs which bound people together, sometimes over a wide area. According to Harari, this is how empires came into being. The early empire builders, such as Hammurabi, used these skills to great effect. The creation of empires became accelerated by the next revolution: the Agricultural Revolution, when ownership of land took on a new importance. Sapiens learnt how to cultivate certain animals and plants so that he did not need to go out foraging any more. This was not particularly good for his health, because he ate a more limited diet, and it wasn’t very good for the flora and fauna, either. A small number of animals (cows, sheep, pigs and chickens) and a few plants (wheat, barley, rice, oats and potatoes) were really sufficient and both domesticated animals and peasants began a life of drudgery from which they have never recovered. Harari uncompromisingly attacks the horrors of factory farming and describes cows as the most miserable creatures on earth.

During the Agricultural Revolution, Sapiens learnt to write and this skill became very useful when he moved on to his next revolution: the Scientific Revolution. Although, throughout history, men and women had made brilliant inventions and discoveries, a change seems to have occurred about five hundred years ago, when sailors started navigating the world and bringing back new information. Inventions came thick and fast and, before long, Sapiens began to think that he could, in time, learn everything about the world himself, rather than leaving it all in the mind of God. This belief in future progress and success had a number of important consequences, not least a dependence on cash and credit. If life was bound to get better rather than worse, and if you could travel the world exploiting the resources of others, why not borrow money now and pay it back when you are richer? And so we gained some new powerful creeds, which haven’t done us much good but which seem to be here to stay – capitalism and consumerism. Harari is fairly disparaging about these, and their cousin, economic growth, but appears to think that they are an inevitable result of Sapiens’ ruthless activities and ambitions over the centuries. He views empires, including the British Empire, in much the same way.

Finally, Harari brings us to the present day, with Sapiens working on artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, cyborgs (beings which combine organic and inorganic parts) and, most scary of all, computers replacing humans. In many ways, Sapiens is a bleak and frightening book, despite the deceptively easy-going style. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Homo Sapiens was the worst thing ever to happen to planet Earth. Not content with destroying almost everything else, he now seems about to destroy himself.

For Christians and members of other religions, there is an even more shocking revelation. According to Harari, all religions and shared beliefs are myths, invented for the purpose of controlling, uniting or (perhaps) inspiring large groups of people. Not only that, but religious groups have also, on occasion, treated other people appallingly in the name of their faith. The only religion which seems to escape Harari’s censure is Buddhism, but that is because it is really a philosophy whose aim is to enable people to achieve happiness through thought processes and without a belief in an external God. That clearly meets with his approval.

For many Christians – probably the majority worldwide – belief in an objective, loving and immanent God is the sine qua non of their faith. They really have no option but to disagree fundamentally with Harari on this aspect of his scholarship and to challenge his arguments – if, indeed, they are arguments rather than statements. Others, swept along by his lucid and persuasive reasoning, and his apparent omniscience, will be left questioning the very essence of their Christian faith. Could he be right? And, if so, where does that leave me? Can the Christian Church accommodate Harari’s conclusions as it did (mostly) those of Darwin? This may be the question that we will all have to answer in the end.

Margery Roberts May 2018

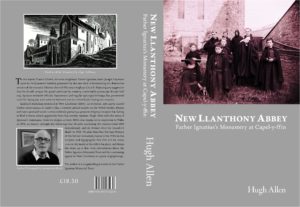

Hugh Allen, New Llanthony Abbey: Father Ignatius’s Monastery at Capel-y-ffin, Tiverton (Peterscourt Press) 2016.

Those who visit this web-site will, no doubt, be familiar with the name of Fr Ignatius. Much has been written over the years on him – true, much was written about him by himself – and whilst the biographies by the Baroness de Bertouch, Donald Attwater, Arthur Calder-Marshall and Peter Anson have much to say about Joseph Leycester Lyne the man, little has been written about those who passed through the monastery at Capel-y-ffin, what went on there on a daily basis, and how Eric Gill came to lease the property in 1924.

Hugh Allen (b.1948) has known Llanthony since childhood, having been taken there on a family drive to places of interest from his Catholic boarding school in Monmouthshire during a Parents’ Weekend in the summer of 1958. The monastery at that time was long run-down, Ignatius’s chapel was a crumbling ruin, and his name a distant memory in the minds of those who lived in the locality. One is tempted to say that this was the expected legacy of a man who was, to say the least, something of a Peter Pan, hopelessly inadequate at both finance and administration, oscillating between high sacramentalism/Ritualism and the evangelical hot gospel (although he seems to have held the two together), living in a medieval dream-world that had never existed with little or no relevance at the end of the nineteenth century, with the “lost boys” who came – and soon left – Capel-y-ffin to serve as novices being drawn from the higher lower class and the lower middle class of late Victorian England. Fortunately, he had his own “Wendy”, in the form of Jeannie Dew (b.1866), known at Capel-y-ffin as Sister Mary Tudfil.

Hugh Allen (b.1948) has known Llanthony since childhood, having been taken there on a family drive to places of interest from his Catholic boarding school in Monmouthshire during a Parents’ Weekend in the summer of 1958. The monastery at that time was long run-down, Ignatius’s chapel was a crumbling ruin, and his name a distant memory in the minds of those who lived in the locality. One is tempted to say that this was the expected legacy of a man who was, to say the least, something of a Peter Pan, hopelessly inadequate at both finance and administration, oscillating between high sacramentalism/Ritualism and the evangelical hot gospel (although he seems to have held the two together), living in a medieval dream-world that had never existed with little or no relevance at the end of the nineteenth century, with the “lost boys” who came – and soon left – Capel-y-ffin to serve as novices being drawn from the higher lower class and the lower middle class of late Victorian England. Fortunately, he had his own “Wendy”, in the form of Jeannie Dew (b.1866), known at Capel-y-ffin as Sister Mary Tudfil.

JESUS ONLY (always in capitals) was Lyne’s motto. It appeared above the altar in the chapel (one is tempted to say “the High Altar”, but though he planned for a much larger building, it never expanded from its aisle-less chancel); it was on the inside covers of the community’s breviaries and on the dormitory bed-spreads. It was his rallying-cry at the end of his fund-raising missions and, whilst one has no doubt that he firmly believed in the slogan, it was probably also his undoing for, had he spent less time travelling to give more effort to structured fund-raising, there is a slight, albeit a very slight, chance that his monastery at Capel-y-ffin might have succeeded. Then there is the miracle of the apparition of Our Lady amidst the rhubarb plant, though the only miracle to me, it seems, is that the community lasted for almost forty years (1870-1908).

Hugh Allen’s book is a masterpiece, embracing decades of research, full of detail relating to the day-to-day running of Capel-y-ffin, how it was staffed, the order in which the various sections of the complex were built and, of greater importance, detailed biographies of the many confused teenagers who came and went as novices. In fact, it covers everything which de Bertouch, Attwater, Calder-Marshall and Anson brushed over in their accounts of Fr Ignatius, probably because, unlike Hugh Allen, they did not have the time to devote to such exhaustive research. By the time that one reaches the end of the book the reader would probably have already summed-up why the venture failed: Ignatius looked for vocations from those who came with adolescent aspirations, received little spiritual guidance and were too frequently admonished for the smallest of transgressions. In short, one cannot build-up an adult religious community by only taking in children and trusting (hoping, rather) that they would develop into medieval monks through rigorous training and strict discipline.

The book is perfectly structured, taking the reader chronologically through Lyne’s childhood, his early years in the Church, his failed attempt to start a Benedictine Priory on Elm Hill, Norwich to his arrival at Llanthony in November 1869. As Peter Anson recorded, Fr Ignatius was convinced that it was his vocation to restore the cloistered Benedictine life in the Church of England. But my goodness, what a time it took to get it into motion! On 22 August 1872 Fr Ignatius laid the foundation stone of his great church. Ten years elapsed before the choir was completed. The nave was never started. And cash-flow was never high, what little money there was coming from Fr Ignatius’ endless preaching tours, as a result of which the handful of monks, mainly novices, at Llanthony were frequently without their spiritual director, suffering the privations of unheated dormitories, harsh winters, spare food (though Ignatius always breakfasted and dined like a prince when in residence) and little to occupy themselves with other than the daily round of offices and services. Is it any wonder that the dwell-time of these aspiring religious was hardly more than six months?

It would be unfair if I was to relate the complexities of the numerous comings and goings of nuns, priests and monastery boys during the thirty-eight years of Llanthony’s existence, and their subsequent history after they had left, for it is this which forms the majority of the narrative, making it a book which it is difficult to put down. In a more enlightened age Fr Ignatius would not have escaped the attentions of a public enquiry. He was a martinet and, yes, cruel in his treatment of the children under his care, a “favourite” soon becoming an outcast, such as the incident when one ravenous child had the audacity to consume a strawberry to stave off his hunger.

Even so, Llanthony became a place of pilgrimage, many wanting to see this strange Benedictine abbot and his medieval community. Visits dramatically increased following a “mystic” appearance of Our Lady in a rhubarb crop some 200 yards from the chapel on 30 August 1880. She appeared again on 4th September, although it was not until 15th September that Ignatius saw the apparition for himself. For ever after 30th August was kept as “The Feast of the Apparition of Our Ladye of Llanthony”. Ignatius himself composed a long eleven-verse processional hymn for the occasions, whose sixth verse runs

‘Mid Llanthony’s silent Valleys,

O’er the meadows cool and green,

Mary comes from Heaven in Beauty,

Haloed as the Angels’ Queen.

Raising up Her hands in blessing,

Thus God willed Her to be seen.

In the fullness of time, a Carrara marble statue of Our Lady, her right hand raised in blessing, was erected on the site of the apparition, which remains the focus of an annual pilgrimage to this day.

In 1881 Fr Ignatius’ small community of nuns moved from Slapton to Llanthony, taking up residence in what can only be described as an army hut, it being a single-storey structure of timber with a corrugated iron roof. This was “The Convent”, housing four nuns, one of whom was designated as Mother. In fact, the community rarely grew above four nuns, and who could blame them, bearing in the mind the conditions in which they were expected to live?

Fr Ignatius died on 16th October 1908 at his sister’s house in Camberley. His funeral, attended by the community and those priests who, over the years, had been wont to say Mass there, took place on 22nd October, the office being sung by the Rev’d W M Magrath, formerly Brother Dunstan. He was buried in front of the chancel step, his grave being twelve feet deep, and the space above the coffin filled with solid masonry and cement. Eighteen months later a tiled cross from Doulton’s of Lambeth was laid, inscribed HIC JACET IGNATIUS JESUS OSB HUIUS DOMUS CONDITOR PRIMUSQUE ABBAS. He lies there still, in the silence of the Black Mountains, now and again punctuated by the bleating of sheep and the call of the night owls.

The community struggled on for another three years but, without a leader of the calibre of Ignatius, it floundered, and most of the surviving brothers annexed themselves to Aelred Carlyle at Caldey. In 1911 Carlyle secured the freehold of the Llanthony property and, finding it surplus to requirements as a monastic institution, it was used by Caldey for a number of purposes, mainly as a holiday home for members of the community. In August 1924 Eric Gill leased the property, and in September 1931 the church, monastery and nine-and-a-half acres of land was purchased from the Caldey monks by Mary Gill for £400.

As Peter Anson was to observe,

“Such was the end of one of the most curious manifestations of the Catholic and Gothic Revivals in the Church of England. The ruined church is symbolic of the failure from the human point of view of Fr Ignatius, ending as it did with the handing over of his beloved monastery to secular owners. There is something inexpressibly tragic about Llanthony.”[1]

Sitting on my bookshelves is a black-bound breviary, 240mm x 190mm, hand-written in English and Welsh, and illustrated by Jeannie Dew (b.1866) who, as Sister Mary Tudfil, entered the Llanthony community as its last nun on 15 February 1898, making her final profession in January 1906 by which time the Llanthony phenomenon was drawing to its close. Rather than take up residence with another Anglican community, Mother Tudfil (as she was by 1910) decided to return to the secular world, continuing to live her monastic vows as a private individual. For the rest of her life she lived in her old family home in Ventnor, dying at the age of 94 on 9 August 1960.

Hugh Allen has written an outstanding book, the photographs being exceptional in their own right. Indeed, one doubts if there is anything further to say about Llanthony, thus it deserves a place on the shelves of all of those interested in the history of the monastic revival in England.

Dr Julian W S Litten FSA

October 2016

Copies of New Llanthony Abbey: Father Ignatius’s Monastery at Capel-y-ffin, may be had of the author at 3 St Peter’s Court, Tiverton, Devon EX16 6NZ at £18.50 + £1.50 p&p. Cheques should be made payable to R.W.H. Allen.

[1] P Anson, The Call of the Cloister, London (S.P.C.K.) 1958, 72.